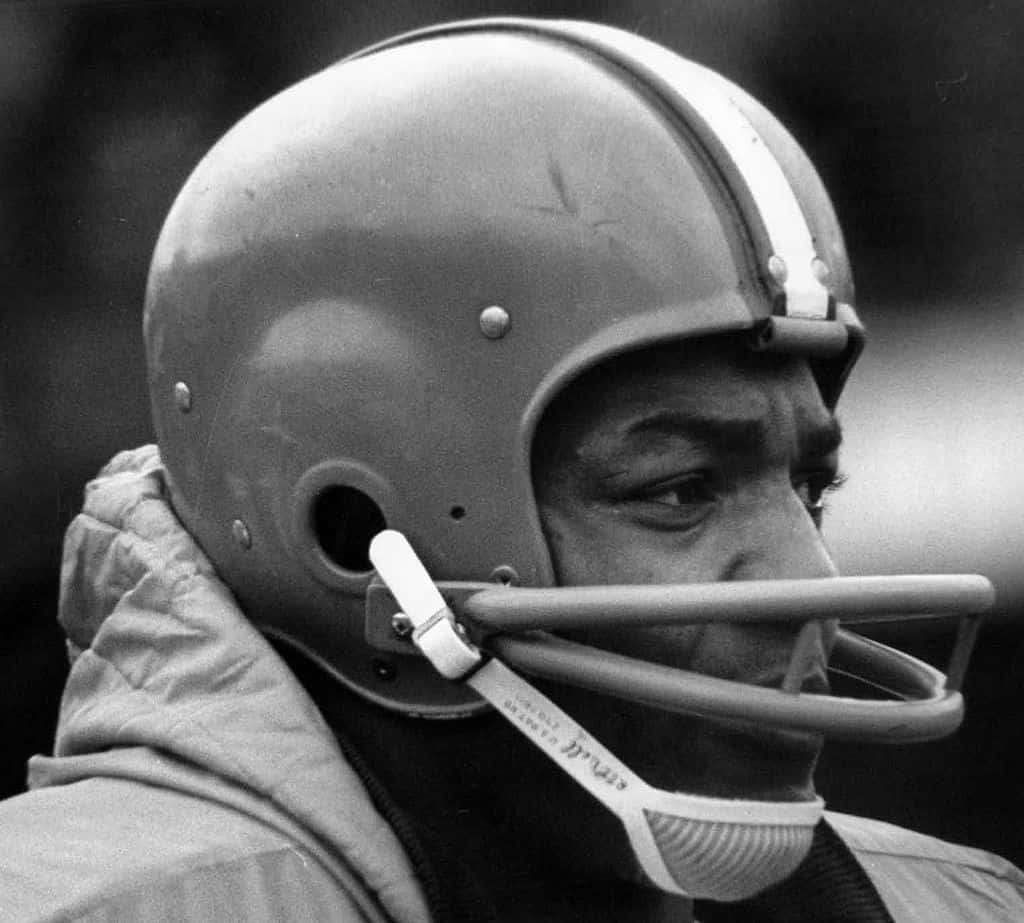

By all accounts, Jim Brown is arguably the greatest running back in Cleveland Browns history.

He’s also been ranked as the top running back (and number four overall player) on the NFL’s top ‘100 players of all time’ list.

Brown was an imposing force on the field and he could also impose his will off the field (sometimes to his detriment).

Since retiring from the game in 1966, he has been an actor, color analyst for NFL games and, perhaps most significantly, a civil rights activist.

Brown continues to be a role model for athletes and activists alike.

Here is a look back at the mercurial life of Jim Brown.

Brown’s Life Growing Up

Jim Brown was born on February 17, 1936 on an island, St. Simons Island to be exact.

February 17, 1936 James Nathaniel “Jim” Brown, hall of fame football player and actor, was born. Brown was selected in the 1957 NFL draft by the Cleveland Browns and over his nine-season professional career was a nine-time Pro Bowl selection and three-time NFL MVP. pic.twitter.com/hZucgfpCG7

— Merrell R. Bennekin (@MerrellBennekin) February 17, 2020

The island, located off the Georgia coast, would not be his home for long.

Brown experienced life’s trials and tribulations from the beginning.

When he was just two months old, Brown’s father, a boxer, took off and never returned.

His mother did not stay long either after taking a job as a maid in Manhasset, New York.

Brown then spent his formative years in the care of his great grandmother.

When he was eight, Brown’s mother sent for him so he could live with her in New York.

Brown arrived in New York and blossomed in Manhasset, although it didn’t start out well at first.

Years ago, Brown shared a recollection with Newsweek magazine about this first day of school in Manhasset.

“My mother had dressed me in new clothes,” he remembered. “That morning when they gave us recess, a black boy made a wisecrack, said I looked ‘pretty,’ and he shoved me. I reacted Georgia-style. I tackled him, pinned him with my knees, punched him. The closed circle of kids watching then started chanting, ‘Dirty fighter, dirty fighter’ I stopped fighting. I was mystified. How did these boys fight up here?”

Attending the mostly white Manhasset High School, Brown not only played football but also competed in baseball, basketball, track, and lacrosse.

Displaying an amazing talent for all the sports he played, Brown averaged 38 points per game in basketball.

He also averaged an astounding 14.9 yards per rushing attempt as a high school senior.

Yes, that Jim Brown. #Manhasset pic.twitter.com/Wh9d1jRiyp

— Andrew Bogusch (@AndrewBogusch) February 21, 2019

Needless to say, the recognition he received from his prowess as an athlete brought college suitors.

Brown’s Time at Syracuse

Brown ended up staying in-state for college and attended Syracuse University.

Just like his time in high school, Brown did not stick only to football in college.

Happy birthday to Jim Brown, February 17, 1936. ????

A four-sport letterman in football, lacrosse, track & field and basketball.

He was commissioned as a second lieutenant through the Army ROTC upon graduation at Syracuse. pic.twitter.com/nXco3Zqt2c

— AFL GODFATHER (@NFLMAVERICK) February 17, 2019

He also ran track and played lacrosse and basketball.

As a basketball player during his sophomore and junior years, Brown averaged 13.1 points per game.

In a game against Sampson Air Force Base during his sophomore year, Brown came off the bench and scored 33 points.

He had planned to return to the team as a senior but he was not allowed to be a starter.

Apparently, at that time, there was an unwritten rule at the university that the basketball team would not start three black players.

Many believe that if Brown had played with the team that year, they would have won the national championship.

Instead, the team lost in the Elite Eight of the NCAA tournament.

Although some people considered Brown’s best sport to be lacrosse, he made a name for himself on the football field.

As Jim Brown is being named the No 1 CFB player, throwback to when Jim Brown dominated lacrosse at Syracuse.

One time Brown scored a hat trick vs Army after competing in a track meet that same day?

As Brown put it him self “Lacrosse is probably the best sport I ever played” pic.twitter.com/yJmII8EXPG— Throwback Sports (@Throwback_Sport) January 14, 2020

When he was a sophomore, Brown was the second-leading rusher on the team.

As a junior, he was the leading rusher with 666 yards and a 5.2 yards per carry average.

As a college senior, Brown was considered to be one of the best, if not the best, running backs in the nation.

That season he played in only eight games yet still rushed for 986 yards.

His average yards per attempt was a school-record 6.2 and he even scored six touchdowns in one game.

In the last game of the season, he rushed for 197 yards, scored six more touchdowns and added seven extra points as a kicker.

Brown finished the year with 14 touchdowns total and was a consensus First-team All-American.

Astoundingly, he finished fifth in the Heisman voting that year.

In the Cotton Bowl against TCU after the season, Brown continued to run wild with 132 yards, three touchdowns, and kicking three extra points.

Not only was he recognized as an All-American in football as a senior, Brown was also recognized as an All-American in lacrosse.

This honor came on the heels of a lacrosse season where he scored 43 goals in 10 games.

Although he did not play the sport professionally after leaving college, Brown was still voted into the Lacrosse Hall of Fame.

Brown in the NFL

Brown’s adroitness on the college football field drew a flock of interest from the NFL.

In the 1957 draft, he was taken by the Cleveland Browns with the 6th overall pick.

ABS honors #BlackHistoryMonth

Today’s showcase player: Jim BrownDrafted 6th overall by the Cleveland Browns in 1957, Brown was a four sport athlete at Syracuse. He is the only man to average 100 rushing ypg over his entire career. He was inducted into 3 HOFs #SB53 pic.twitter.com/SD2DSmCOwD

— The Association for the Business of Sports (@OhioStateABS) February 3, 2019

Jim Brown rookie contract $12,000 pic.twitter.com/U2ayXABWKX

— ??? ???????? ???????? (@NFL_Journal) April 26, 2020

It didn’t take long for the league to see Brown’s talent first-hand.

In his ninth game, he rushed for 237 yards against the Los Angeles Rams.

That performance set an NFL single-game record that stood for 16 years before being broken by O.J. Simpson.

His mark also set an NFL rookie record that remained in place for 40 years.

Brown ended his rookie season with 942 rushing yards, nine rushing touchdowns, and a receiving touchdown.

In his second pro season, Brown set an NFL single-season rushing record with 1,527 yards (which he would break again in 1963).

Oct 20,1963 – Jim Brown, #Cleveland Browns sets #NFL single-season rushing record, 1,863 yds #browns #history pic.twitter.com/nzi4RxWw12

— Richard Krivo (@RKrivoFX) October 20, 2015

At the time, the NFL season was only 12 games.

Many modern historians wonder what his final tally would have been with a modern 16 game regular season.

His rushing total in 1958 far surpassed the former record of 1,156 yards set by Steve Van Buren of the Eagles in 1949.

In 1958, Brown also scored a whopping 17 rushing scores and one receiving touchdown.

In 1964, Cleveland had a good year, finishing 10-3-1.

Brown continued to rack up huge numbers and finished the season with 1,446 yards at a 5.2 yards-per-carry clip.

Although the team had Brown pacing them with his legs, Cleveland was also dangerous through the air.

Their first-round draft pick in 1964 was Ohio State’s Paul Warfield.

Warfield and Browns quarterback Frank Ryan kept defenses honest as Ryan passed for over 2,400 yards and Warfield hauled in 52 receptions and nine scores.

The trio led the team into the championship game against the Baltimore Colts.

Just as it is typical in modern times, media pundits resoundingly picked the Colts to win the game after Baltimore finished the ‘64 season at 12-2.

The Colts were confident in their own trio of Johnny Unitas, Lenny Moore, and John Mackey leading the team to victory.

However, Brown was not fazed and, before the game, was quoted as saying, “We’re going to kick their [butt] today.”

Sure enough, Brown backed up his bold statement with 114 yards rushing on the way to a 27-0 pasting of the favored Colts.

Jim brown in the 64’ championship game on December 27th at municipal stadium the Cleveland Browns defeated the Baltimore Colts 27-0 on this day brown had 114 yards on 27 attempts @Browns pic.twitter.com/UuIuxIyXAv

— Aaron Wood (@Aaron_330) April 21, 2020

Ryan contributed 206 passing yards and three touchdown tosses to receiver Gary Collins.

The win was the team’s first championship game victory since 1955.

In Brown’s final season of 1965, Cleveland finished 11-3 and returned to the championship game against Green Bay.

This time, however, the team was not victorious and lost to the Pack 23-12.

Brown was bottled up by Green Bay and rushed for only 50 yards.

Brown put up staggering numbers throughout his nine-year NFL career.

The only other season he rushed for under 1,000 yards (besides his rookie season) was in 1962, his sixth year in the league.

In that season, he finished four yards short of the 1,000 mark (996).

When he retired after the 1965 season, he led the NFL in numerous categories.

Among the categories were: single-season record holder (1,863 in 1963), career rushing yards (12,312 yards), all-time leader in rushing scores (106), and total touchdowns (126).

He was also the all-time leader in all-purpose yards with 15,549.

Jim Brown #Browns

pic.twitter.com/JseMPocCO8— CleWest (@erjmanlasvegas) March 22, 2020

In his somewhat short pro career, Brown led the NFL in rushing eight times.

His final game was the 1966 Pro Bowl where he scored three touchdowns.

As he was walking away from the game, fans and fellow pros alike were upset as to why Brown was calling it a career.

After all, in his final season of 1965, he rushed for 1,544 yards (the second-most of his career) and had 21 total scores.

Brown was also the NFL MVP that season and the team went to the championship game.

Even more baffling, Brown was not yet 30 years old.

As it turns out, history has shown us that Brown’s retirement had nothing to do with injuries or a decline in athletic ability.

Early Film Roles and “The Dirty Dozen”

Just before the 1964 season, Brown filmed the role of a Buffalo Soldier in the movie “Rio Conchos.”

When the movie premiered in Cleveland, Brown viewed it with many of his teammates.

Critics panned the movie but said Brown’s acting in the film was “serviceable.”

RIP #StuartWhitman (February 1, 1928 – March 16, 2020)

Rio Conchos, 1964, directed by Gordon Douglas.

Richard Boone, Stuart Whitman and Jim Brown.

Opening scene. pic.twitter.com/NH8yW2PVWB— Sergio Rodríguez (@Sergiofordy) March 19, 2020

In the early months of 1966, Brown was working on his next movie, “The Dirty Dozen.”

The film is a WWII story about 12 convicts selected for a special mission to assassinate German officers before the D-Day invasion.

@Pinceladasdcine Clint Walker and Jim Brown.”The Dirty Dozen”.#cinema pic.twitter.com/uKAQkNttpi

— Tom’s Old Days (@sigg20) January 30, 2016

There were numerous production delays during the filming because of weather.

Those delays threatened to cause Brown to miss part of training camp and that caught the attention of former team owner Art Modell.

Modell threatened Brown with a $1,500 fine for every week of training camp he missed.

To show the world, and Brown himself, that he meant business, Modell sent out a message:

“’No veteran Browns player has been granted or will be given permission to report late to our training camp at Hiram College — and this includes Jim Brown. Should Jim fail to report to Hiram at check-in time deadline, which is Sunday, July 17, then I will have no alternative to suspend him without pay. I recognize the complex problems of the motion picture business, having spent several years in the industry. However, in all fairness to everyone connected with the Browns — the coaching staff, the players and most important of all, our many faithful fans — I feel compelled to say that I will have to take such action should Jim be absent on July 17.”

Brown had already said that the ‘66 season would be his last and, instead of haggling with Modell, declared his retirement while still on the set of the movie.

Hold my beer.https://t.co/94SVdKJhGe

— Mark Standriff (@MarkStandriff) April 16, 2020

Modell later admitted in the book When All the World was Browns Town that he had overplayed his hand with Brown.

“I may have acted hastily (with Brown) in 1966. If I had told him to just forget training camp and show up when he could, I think he would have returned. But it wasn’t fair to the coaches and players (for Brown to miss camp).”

Brown Continues His Acting Career

At 30 years old, Brown was finished playing sports for the first time in his life. However, he kept plenty occupied with his work in the film industry.

The same year he filmed “The Dirty Dozen,” Brown was also seen in an episode of the television series “I Spy.”

The following year he took larger roles in the movies “Ice Station Zebra,” “Dark of the Sun,” and “The Split.”

When the 1970s dawned, Brown got involved with several ‘Blaxploitation’ films that were a popular genre at the time.

Entertaining and well-directed, “Black Gunn” (1972) is a perfect #blaxploitation flick with badass Jim Brown in the lead. #movies #cinema pic.twitter.com/EuZS7I51qF

— matte (Matt Cote) (@m77oz) September 16, 2017

Blaxploitation was termed as a way to describe how the roles in these films were made up largely of black actors who played controversial characters.

While the films received some acclaim, they also received a fair share of backlash.

Many critics said Blaxploitation was a means to show stereotyped black actors playing roles that entailed poor and questionable motives.

Brown paid no attention to the critics and appeared in at least a half dozen such movies.

As the genre ebbed in the mid-70s, Brown found work in other projects.

For the next few decades, Brown would appear in numerous television and movie roles.

Most notably, he played ‘Fireball’ in the Arnold Schwarzenegger film

“The Running Man” and ‘Slammer’ in the movie “I’m Gonna Git You Sucka”, both in the late 1980s.

Jim Brown was born on this day in 1936 – appeared in two great 80s roles, Fireball in The Running Man (https://t.co/G6zfaGQY60) and Slammer in I’m Gonna Git You Sucka (https://t.co/MS3fMx2yL1) pic.twitter.com/SBByiCy2n1

— Betamax Video Club (@BetamaxPod) February 17, 2020

Before the century came to a close, Brown could be seen playing football coach ‘Montezuma Monroe’ alongside actor Al Pacino in “Any Given Sunday.”

As the years continue to roll along, Brown has appeared less and less in the film and television industry.

Don’t Call it a Comeback…

Although Brown was highly involved in his television and movie roles, he still kept his toe in the sports world.

In 1978, he joined CBS as a color analyst as part of a trio that included Vin Scully and George Allen.

Brown also occasionally announced boxing matches on television and, later, pay-per-view Ultimate Fighting Championships.

In 1983, Brown was at the forefront of NFL news when he announced he was coming back to play in the league.

Despite the fact that he had been retired for 17 years did not matter.

Brown was determined not to let then Steelers running back Franco Harris take his all-time rushing title.

He made it widely known that he did not care for Harris’ running style as Harris had a tendency to step out of bounds to avoid big hits and potential injuries.

In contrast, Brown had played with a style of straight ahead, brute force.

“I never ran out of bounds. I would drop my shoulder and tried to run through the tackle. …. You never know when you may break one all the way.”

-Jim Brown pic.twitter.com/4Zk2UqK9xS— John Hines (@JohnHines66) November 19, 2019

So, Brown signed with the Los Angeles Raiders and was ready to step in to play and add yards to his career totals.

Although he never did play in a game for the Raiders, he still had a deep disdain for Harris.

After Harris retired as a member of the Seattle Seahawks in 1984, Brown wasn’t through with him.

Harris had not surpassed Brown’s rushing total (Walter Payton would eclipse the total in 1984) but Brown still wanted to show Harris that he was a better athlete.

In a nationally televised event, Harris and Brown ran against each other to see who had the faster 40 yard dash time.

It should be noted that, on the day of the event, Brown was 47 years old and Harris was 34.

In the end, it wasn’t even close as Harris finished with a 5.16 time and Brown trailing at 5.72.

After being released by the Steelers in 1984, Franco Harris signed with the Seahawks. He played eight games, gaining 170 yards before retiring. He was 192 yards short of Jim Brown’s record. Although, he did beat Brown in the ‘I Challenge You’ 40 yard dash. pic.twitter.com/Pypspy88bj

— One Team Too Many (@OneTeamTooMany) February 1, 2020

“I wore 32 on my back to be like Jim Brown.”

– HOFer Franco Harris on @JimBrownNFL32 #JimBrownAt80 pic.twitter.com/nhydygObVj

— NFL Network (@nflnetwork) February 18, 2016

Brown remained active in sports for decades.

In 2008, he was named as an executive advisor for the Browns, helping to build relationships with Browns players and assisting with Cleveland’s player programs department.

Going back to his roots, Brown bought a stake as a part-owner for the New York Lizards of Major League Lacrosse in 2012.

Then, in 2013, Brown was named as a special advisor for the Browns.

Legal Issues

Unfortunately, not all news regarding Brown has been good news.

His first wife, Sue, filed for divorce in 1968, nine years after they were married.

In her reason for wanting a divorce, she charged Brown with “gross neglect.”

The couple had three children together, Kim, Kevin, and James Jr.

Terms for the divorce stipulated Brown pay alimony and weekly child support.

In 1965, while still married to his first wife, Brown was arrested in a hotel room for assault and battery against an 18-year-old named Brenda Ayres, although he was acquitted of the charges.

Only a year later, Brown had to fight an allegation by Ayres that he fathered her child.

In 1968, model Eva Bohn-Chin was found beneath the balcony of Brown’s second-floor apartment.

Apparently, Brown had been dating Bohn-Chin and she had become jealous over an affair he was having with social activist Gloria Steinem.

The two argued about the affair and Brown became physical.

He was charged with assault to commit murder in the case.

However, Bohn-Chin refused to cooperate with the prosecutor’s office involved in the case, so Brown’s charges were dismissed.

Brown did have to pay a $300 fine due to an altercation with a deputy sheriff who was investigating the case.

And if you watch “Jim Brown: All-American,” it’s pretty much impossible to accept his version of events regarding Eva Bohn-Chin. pic.twitter.com/bW8hl9Cxqp

— Joel D. Anderson (@byjoelanderson) October 9, 2018

Although he was not charged, Brown knew that he had done wrong, not by trying to hurt Bohn-Chin, but by, “Slapping her.”

He later admitted in his memoir that he knew this behavior was wrong.

“I have also slapped other women,” he wrote. “And I never should have, and I never should have slapped Eva, no matter how crazy we were at the time. I don’t think any man should slap a woman. In a perfect world, I don’t think any man should slap anyone. . . . I don’t start fights, but sometimes I don’t walk away from them. It hasn’t happened in a long time, but it’s happened, and I regret those times. I should have been more in control of myself, stronger, more adult.”

In 1969, Brown was embroiled in a road rage incident and charged with assault and battery.

He was found not guilty of the charge a year later.

Brown then met an 18-year-old college student named Diane Stanley in 1973 and, months later, proposed to her.

They broke off their engagement the following year.

Roughly a year after that, Brown was sentenced to a day in jail, two years probation, and a $500 fine for beating and choking Frank Snow, his golfing partner.

A decade later, in 1985, Brown made headlines again when he was charged with raping a 33-year-old woman.

The charges in that case were dismissed as well.

The following year, Brown assaulted his then fiancee Debra Clark and was arrested.

When Clark refused to press charges, Brown was released from jail.

Brown’s internal opinions (and not-so-subtle view) about women was made known four years later.

In 1989, The LA Times newspaper interviewed Brown after the release of his memoir, “Out of Bounds.”

In the article, Brown is quoted comparing women to fruit and meat.

“I prefer girls who are young,” he says in “Out of Bounds,” his hot-off-the-press memoir. “When I eat a peach, I don’t want it overripe. I want that peach when it’s peaking.” Or to put it another way, “If I wake up in the morning, I hunger for crab, then I don’t want steak.” Steak being a woman who is older, say over 25.

In 1997, Brown married for the second time to Monique Brown.

Two years later Brown was arrested yet again and charged with making terrorist threats against his wife.

That same year, Brown smashed a window of his wife’s car and was charged with vandalism.

After this latest incident, Brown was given three years probation, one year of domestic violence counseling, 400 hours of community service (or 40 hours on a work crew), and charged with an $1,800 fine.

Brown proceeded to ignore the terms of his judgment and was sentenced to six months in jail in 2000.

He didn’t start serving time until 2002 when he refused to undergo counseling and partake in community service.

In the end, he only served three of the six months in jail.

Brown later admitted his issues with women in an Esquire Magazine article.

“I’ve done things I’m not particularly proud of,” he said, “but at least I’m honest enough to talk about them.”

Brown as a Civil Activist

Although he may have had serious issues with women, Brown did make time to mentor minorities during and after his playing career.

While playing in Cleveland, Brown founded the Negro Industrial Economic Union (later changed to Black Economic Union, or BEU).

The BEU used professional athletes as facilitators in establishing black-run enterprises, urban athletic clubs, and youth motivation programs.

In addition to marching alongside Bill Russell in many civil rights protests in the 1960s, Jim Brown also started the Black Economic Union, which helped black professional athletes establish their own businesses after their playing careers ended. pic.twitter.com/e6omsp4mVA

— Black Athlete Protests (@3030Auburn) November 14, 2018

A few years after retiring, Brown, Lew Alcindor (eventually known as Kareem Abdul-Jabbar), Bill Russell and numerous other black athletes came together to pledge their support for Muhammad Ali.

The assembled group met at Brown’s BEU headquarters in Cleveland.

The meeting, dubbed the “Ali Summit” was initially convened to try and persuade Ali to enter the military and accept a deal with the government whipped up by boxing promoter Bob Arum.

The Ali Summit in Cleveland, 1967

Front row: Bill Russell, Boston Celtics; Ali; Jim Brown and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar.

Back row to follow pic.twitter.com/Pb1UsgwOSw— Rabih Alameddine (@rabihalameddine) September 26, 2017

Arum, along with others, had convinced the government to drop Ali’s “draft dodger” charges if Ali joined the military and performed boxing exhibitions for U.S. troops.

Years later, it came to light that some of the men in the room actually had financial reasons to want Ali to accept the deal.

However, he stuck to his proverbial guns and refused to enter the military.

Brown and the other black athletes assembled did not gain any possible monetary kickback because of Ali’s stance.

However, they discovered a new found respect for what Ali stood for.

The summit ended up being a show of solidarity for Ali and for religious freedom.

At that point moving forward, the group became one voice in standing up to the government and their view that the government was targeting Ali simply because he was black.

Some time later, well after the Ali Summit, the BEU closed shop.

Brown then brought the BEU idea to the Coors Golden Door program as well as Jobs Plus.

In 1986 Brown started Vital Issues, a new program that taught life management skills and personal growth techniques.

Specifically, this program was implemented to reach inner-city gang members and prison inmates.

Two years later, Vital Issues was rebranded Amer-I-Can.

In 1988 Jim Brown founded Amer-I-Can, an org that helps gang members & at-risk youths. https://t.co/0wZFth9oPd pic.twitter.com/B3A4YoE0eY

— Cleveland Browns (@Browns) February 16, 2016

Found on the Amer-I-Can web page, the program goal specifically is to, “…help enable individuals to meet their academic potential, to conform their behavior to acceptable society standards, and to improve the quality of their lives by equipping them with the critical life management skills to confidently and successfully contribute to society.”

When meeting with members of his program, Brown can be found teaching lessons from his home near Los Angeles.

He believes that failure in personal development and lack of self-esteem are at the root of the problems many young, black people face.

To rehabilitate their own image and improve their lives, Brown believes Amer-I-Can (in theory) will work, “…by enlarging the scope of individual lives, by introducing them to self-determination techniques, by motivating them with goals, by showing them how to improve and achieve success and financial stability, we will save lives that now seem to be lost.”

Jim Brown’s Amer-I-Can makes a difference https://t.co/rJvtSdwz9L pic.twitter.com/R1a9WqYwQq

— ASCS Awakening the compassionate heart in athletes (@ascs98) June 20, 2016

In 1992, the program received a $1 million grant to expand to San Francisco and Cleveland.

In addition to his work with Amer-I-Can, Brown’s civic programs expanded in the 1980’s.

No stranger to the television and movie industry, he founded Ocean Productions to facilitate minorities working in movie making.

Brown has been hands-on with each of his programs and encourages all athletes to get involved in their communities.

Specifically, he urges his fellow athletes to do more than “make gestures” when confronting societal issues.

Brown has publicly made known what he’s hoped his programs will accomplish.

“For too long black Americans have been chasing the shadow of the rabbit. It’s time for us to start chasing the rabbit, not his shadow.”

Brown ultimately wants to give minorities the opportunity and chance to succeed.

“The young black male is the most powerful source of energy and change we have. My hope is to start a direction where these young men will be given respect and taught how to utilize it.”

In Conclusion…

Brown turned 84 years young in February yet he remains as active as possible.

His appearances have been minimal and have not garnered the same notoriety as in his younger days.

However, in 2018 Brown and rap star Kanye West visited the White House to meet with President Donald Trump.

WATCH: Trump meets with Kanye West and former NFL player Jim Brown in the Oval Office #tictocnews pic.twitter.com/jVcwIG0FZ2

— QuickTake by Bloomberg (@QuickTake) October 11, 2018

The meeting served as an opportunity for Brown and West to share their views about what problems need to be addressed in America.

Both men received backlash for seeking an audience with the polarizing president.

However, Brown defended why he and West met with Trump.

“This is the President of the United States. He allowed me to be invited to his territory, he treated us beautifully, and he shared some thoughts, and he will be open to talking when I get back to him. That’s the best he could do for me.”

Although Brown’s actions and words have also made him a polarizing figure through the decades, he views his life as one well-lived.

“When I lay down, I think of all the experiences I’ve had and the respect that I’ve gotten. That’s my glory.”